A quiet strength: Esther Butler’s story of love, loss and grace

Through Depression-era hardship, widowhood twice over, and quiet resilience, she built a life rooted in devotion and practicality.

Adapted from a biography by her son Bob Dailey, with additional research and context.

Esther Pauline Butler was born in 1916, just three years before American women won the right to vote. She grew up in the shadow of World War I, came of age during the Great Depression, and raised a family through World War II and the Cold War era. Her life, like that of so many women of her generation, was shaped by a century of transformation — but her values remained rooted in faith, family, and quiet resilience.

She spent her early childhood in Gerrardstown, West Virginia, one of nine children born to a working-class family. Her father labored seasonally in the fruit orchards of the Shenandoah Valley, a region known for its apple production, and later took part in New Deal-era infrastructure projects, helping to build the roads that would knit rural America more tightly together.

By the time Esther was 10, the Butler family had moved to Jefferson Avenue in Pikeside. The move likely reflected the economic push and pull of rural-to-urban migration that was common in early 20th-century Appalachia, as families sought steadier work and access to schools and services. Esther would go on to graduate from Martinsburg High School — an achievement not taken for granted by many in her working-class community.

After high school, she found employment at the Interwoven Stocking Company, a factory in Martinsburg that was once the largest men’s hosiery mill in the world. It was hard, repetitive work — and part of a larger industrial economy that gave women limited but critical paths to financial independence before marriage.

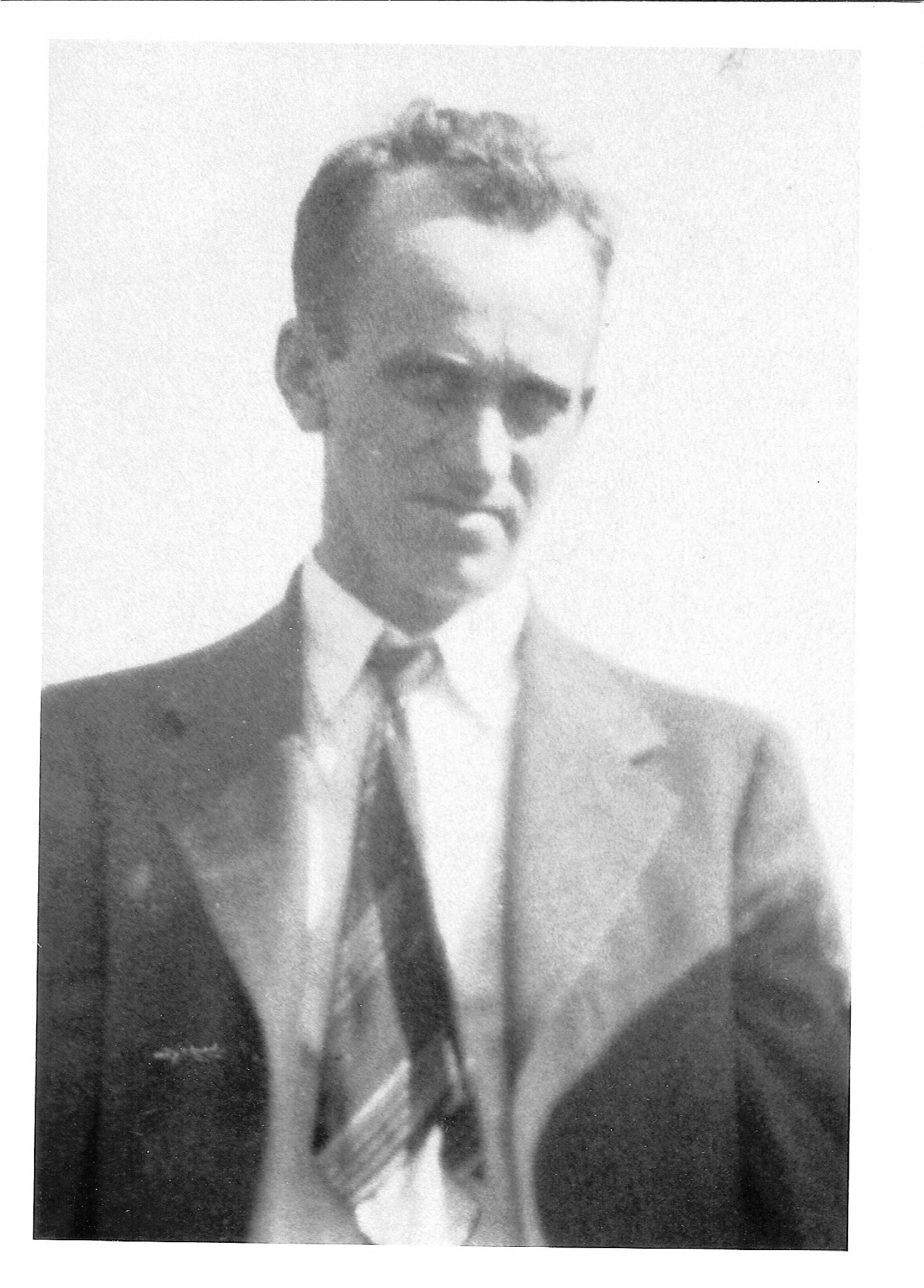

During the Great Depression, social customs around courtship were modest by necessity. It was in this era that Esther met James “Hersel” Dailey, a farmer and truck driver from Charles Town. Their romance was typical of the time — simple and sincere. They went out often for coffee, a small but meaningful luxury during years of widespread economic hardship.

In 1940, when Esther was 24 and Hersel was 30, the couple traveled with her sister Velma and Velma’s fiancé Harry Ott to Hagerstown, Maryland. There, in a joint ceremony before a justice of the peace, both couples were married — a practical and cost-effective option common among working families of the time.

Newlywed life

They settled into a shared home on Jefferson Avenue in Charles Town — the Otts upstairs, the Daileys downstairs. Though the house had running water, it lacked an indoor bathroom. The privy was out back, near the chicken house.

Esther and Velma became pregnant with their first children at nearly the same time. Esther’s firstborn arrived in February 1942, Velma’s in June. By then, World War II was underway, and life in small-town America was marked by both rationing and a sense of shared purpose.

Not long after the new babies’ arrival, the Otts moved to Bolivar, and the Daileys remained in the house. Hersel eventually built an indoor bathroom. The couple had a total of four sons. Esther, like most women of her generation, became a full-time homemaker. Cooking, laundry, and childrearing defined her daily life, along with an ethic of thrift, order, and perseverance.

Monday was laundry day. Clothes were washed and then hung to dry on lines — work that occupied much of the day. Everything was then ironed. It’s just what women did back then, to ensure they and their families looked presentable.

A devastating loss

Tragedy struck in 1958 when Hersel died suddenly, leaving Esther a widow at 42 with four sons ranging in age from 4 to 16.

This would have been a devastating blow in any era, but especially so in a time when widowhood could lead to immediate financial precarity. Yet Esther carried on. Like many widows in mid-century America, she entered the workforce in a way that balanced income with continued parenting.

She took a job as a cook at Wright Denny Elementary School, which allowed her to be home before the school buses returned. She later worked cleaning rooms at the Town House Motor Lodge and then took a position at Doubleday Publishers in Berryville — part of a growing female labor force that supported the post-war economy in America.

Eventually, Esther found stable employment at Stuck and Alger’s Drug Store in Charles Town. She began at the food counter and worked her way up to cashier and clerk. She remained until her retirement.

Five years after losing Hersel, Esther remarried. Her youngest son, Mark, was working at the Tastee Freeze when he introduced his mother to Jacob “Sam” Hehle. The couple married at the Brethren Church in Pikeside and continued living at 215 Jefferson Avenue. Together, they saw Mark graduate from high school and college — a major milestone in a family that had worked so hard for every step forward.

Esther was widowed again around age 60. Though her sons were grown, she remained in the family home. It became harder to manage as she aged, but help came from her brother-in-law Tom Henry, known affectionately as “Big Tom,” who often stepped in to offer comfort and practical support. As her son Bob remembered:

“When nights looked pretty dreary and things were closing in, Mom could call Big Tom, who would drive in from Summit Point to sit at the kitchen table, drink coffee, and talk her through the situation. Later, she would just wonder how she was able to get through all those years.”

Her children, though grown, continued to return for holidays. The kitchen — always the heart of the house — remained the place for food, conversation, card games, and companionship. Family, faith, and routine were the constants that grounded her.

Esther’s spirituality ran deep. She was a regular churchgoer. Her favorite Bible chapter was Ruth — a woman of loyalty and quiet strength, much like herself. Gospel music was her favorite, especially when sung by her nieces, the Ott sisters. She enjoyed visits from her sister Murle, who would come in from Inwood on Saturdays to help with the housework.

Later in life, Esther took trips with groups of fellow seniors. She planned her trips carefully, laying out her clothes weeks in advance — the same thoughtful planning she brought to every season of her life.

In the same spirit of preparation, she pre-arranged her funeral — choosing her casket, burial clothes, and even the program. She wanted to leave nothing undone.

Esther died 25 years ago today on July 5, 2000, at Jefferson Memorial Hospital. She was 83.

One of her favorite poems was "Drinking From My Saucer," a simple but profound reflection on gratitude — a fitting epitaph for a woman who gave so much and asked so little.

I've never made a fortune,

And I'll never make one now.

But it doesn't really matter,

'Cause I'm happy anyhow.As I go along my journey,

I'm reaping better than I've sowed—

I'm drinking from the saucer

'Cause my cup has overflowed.I don't have a lot of riches,

And sometimes the going's tough.

But while I've got my kids to love me,

I think I'm rich enough.I'll just thank God for the blessings

That His mercy has bestowed—

I'm drinking from the saucer

'Cause my cup has overflowed.If You give me strength and courage

When the way grows steep and rough,

I'll not ask for other blessings—

I'm already blessed enough.May I never be too busy

To help bear another's load.

Then I'll be drinking from the saucer

'Cause my cup has overflowed.