The Greenfield family of Berkeley County: A story of hardship, survival, and the weight of history

A journey through poverty, parenthood, and perseverance

John Cleveland Greenfield was born in 1884 in Berkeley County, the third son of a Pennsylvania-born father who had fought for the Union during the Civil War — a conflict that had divided families and neighbors in this region. The legacy of war, poverty and geographic isolation deeply shaped local life in the late 19th century.

John’s ancestry included the Ridenour and Mansfield families — names rooted in the patchwork of German and English settlers who had come to the Shenandoah Valley in the 18th century seeking land and religious freedom. His family would have lived by the rhythms of the seasons: planting, harvesting, canning, chopping wood, and tending livestock.

John lost his mother when he was only 8 years old, a formative trauma that likely shaped his emotional development. At the time, childhood death and maternal mortality were tragically common, and grief was often borne silently, without psychological support. Boys were taught to be stoic, even in loss.

A youth marked by instability

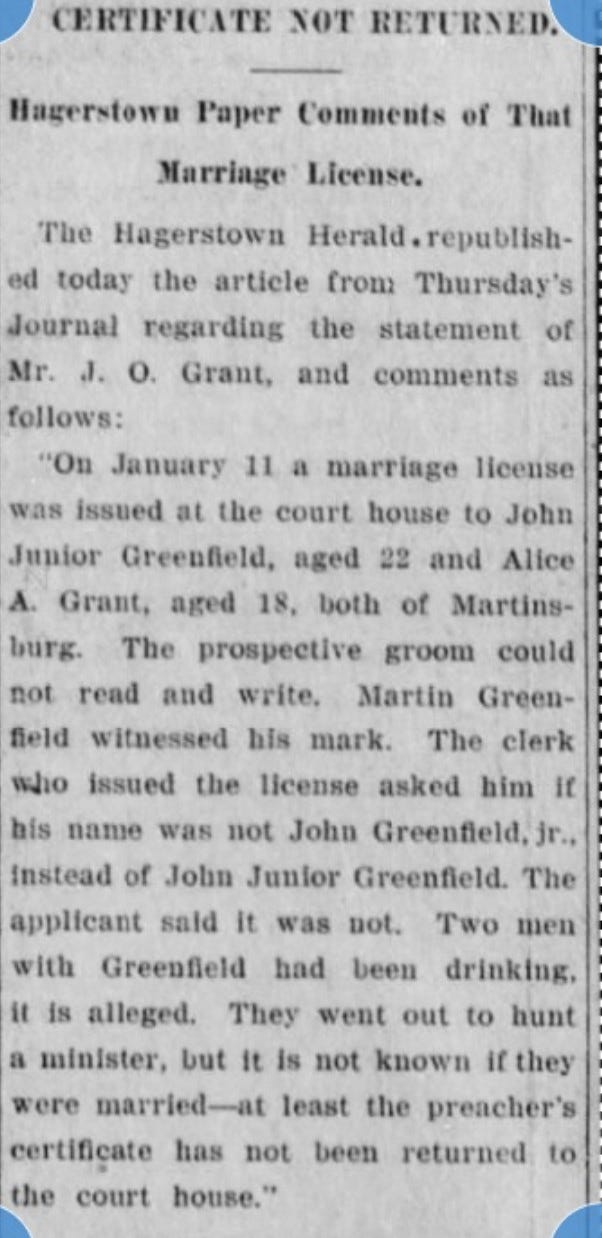

In 1908, at age 23, John sought a marriage license with a 16-year-old girl named Alice Grant, claiming she was 18. No marriage record appears, suggesting the union never took place.

A year later, at age 24, he married Daisy Myers, who had just turned 13. While this shocks modern sensibilities, marriages involving young teenage girls were not unheard of in early 20th-century Appalachia.

Daisy — whose lineage included the Collins, Butts, Pain, and Lamon families — was only 22 days old when her mother died. Daisy was raised by her Aunt Sallie Helferstay.

Daisy gave birth to her first child at 16 and spent the next 18 years in near-constant pregnancy. Between the ages of 15 and 34, she delivered at least twelve children.

But childbirth was deadly. Daisy died one day after delivering her final baby, Joseph (“Joe Bud”), a fate common in a time when poor rural women had limited access to medical care. Maternal mortality rates in Appalachia were especially high due to malnutrition, lack of prenatal care, and poor sanitary conditions during home births.

John never remarried. As a widower, he raised the children alone, or at least the older ones. The same aunt who had raised Daisy, Sallie, now took care of Daisy and John’s younger children until her death seven years later in 1937.

By the early 1950s, two decades after Daisy’s death, John was still living in Gerrardstown, working as an orchard hand alongside his adult sons, John Jr., a carpenter, and Joe, the last-born child. John Sr. died in 1958 at age 74.

Patterns of loss: Health, labor, and shortened lives

The Greenfield children bore the imprint of generational hardship. Several sons died young by today’s standards — at 62, 60, 56, 49, and 47. Their early deaths likely reflect the physical wear of manual labor, poor access to healthcare, and high rates of tobacco, alcohol, and untreated illness that plagued rural Appalachian men.

Most of the Greenfield daughters did not fare any better. One died in infancy, another at 5 years old, and two others in their 30s.

Ruth and Lara: Sisters who endured

Only two of the twelve siblings lived past age 70: Ruth (born 1913, lived to 74) and Lara (born 1915, lived to 77).

Ruth married Riley Butts, a brakeman for the B&O Railroad, one of the region’s major employers. The railroad offered a rare kind of security, with wages and housing slightly above subsistence. Ruth also worked, which was common for Martinsburg women during the Depression and WWII — she took a job as a knitter at the hosiery mill, a hub of female labor in the 1930s and '40s.

They lived at 310 East Martin Street in Martinsburg and had one daughter, Margaret (who sadly echoed the family’s pattern: She and her husband both died in their 60s, and their two children passed in their 40s and 50s).

Lara married Charles Leroy Bowers and settled near Falling Waters, just off U.S. Route 11. Though they lost a stillborn baby in 1944, four of their children survived. The Bowers family represents a quiet continuity — people who stayed close to the land and to each other, enduring in spite of loss.

Social and emotional echoes

The Greenfield family’s story is emblematic of a wider Appalachian experience: early marriage, large families, deep grief, hard physical labor, and an unspoken resilience. In such communities, people rarely talked about trauma — they just kept going. Emotional survival meant burying the past, keeping your head down, and trusting in faith, family, and work.

To reflect on the Greenfield family is to understand a slice of American history too often overlooked: the lives of rural, working-class families in the shadow of war, poverty, and progress that rarely reached them. Their story isn’t just one of suffering — it’s one of endurance, sacrifice, and love expressed through labor. And while modern eyes might view some of these patterns with discomfort, they also reflect the incredible will it took to survive — and raise families — in a world that was often unforgiving.